An editing-based workflow for writing academic papers

Update 2023-09-11 — Light editing.

Update 2022-08-01 — Editing.

In this post I describe my process for writing academic papers, more or less from start to finish, with examples from a chapter I recently finished for Routledge Handbook of linguistic prescriptivism. This post is intended primarily for students as a hands-on example of how one might go about writing a paper or a thesis, of the steps involved, and of the amount of work one might expect to have to put into it. The post also demonstrates a way of thinking about editing as a core part of thinking.

Writing down advanced and complicated ideas is not simply a matter of putting your thoughts to text from start to finish; it entails carefully weighing and testing formulations, word choices, text structures, and what to cite and how. You rarely make the right choice the first time around, and you typically have to write it down to find out if it works. Choices you do also affect other parts of the paper; you don’t want to repeat yourself unnecessarily or use inconsistent terminology, for example. And since you cannot hold the entire paper in your head at once, these things will pop up in later editing passes. Also, the logically exact and unambiguous formulations required in good scientific writing, where everything is made completely explicit, is in many ways a counterintuitive and unfamiliar way of using language and quite different form every-day and literary modes of expression. For all these reasons, academic writing inevitably involves a lot of test-writing to see what works, and a lot of editing to make it work. This process is labor-intensive, but also highly rewarding and interesting.

Writing a thesis or a first longer research paper is for many students an emotionally taxing and stressful task. This stress often comes from not being familiar with the process and the intermediate steps between the initial idea and the finished text, and from not knowing how much time and effort to expect to put into it. This makes it difficult to evaluate ones progress, and it is easy to (erroneously) assume that since you have to redo a lot of rewriting, you must be doing something wrong. The more times you go through this entire process from start to finish, the more familiar you become with it and with its different phases. You learn that numerous cycles of rewriting and editing are a natural part of good academic writing. With this familiarity you also become more relaxed with the whole process and it gets more enjoyable. I hope this post can be a shortcut to reaching that familiarity.

The writing process

My process for writing academic papers includes multiple passes of printing and editing by hand. I find reading the printed text, as opposed to reading it on screen, puts it in a different light, making it easier to spot things that need to be changed. I also like the physicality of it, feeling the resistance of the pen against the paper and seeing the margins being filled out with notes, arrows, and doodles. Working with pen and paper also gives some welcome time away from the computer screen.

After the initial idea, my writing of a paper can be described as five steps, all described in detail below:

- conceptualization and structuring

- research and note-taking

- first write-up

- editing

- proof-reading

Some of these are repeated several times. Step 4 is the most involved in terms of writing and is the most cyclical, and accordingly gets it gets the most space here.

These steps are not intended to be a handbook or a set of prescriptive rules for how best to write a paper. It is only an example of one way to go about it. Other researchers may have developed other strategies and routines that work well, or better, for them than this does to me.

Step 1: Conceptualization and structure

When I only have the idea of the paper, before even doing research, I write down the main structure of the paper in the form of section headings, sometimes with short notes in the form of bullet-lists under each heading of what that section should include. Crucially, these notes include the research question or the stated the aim of the paper. This gives me an opportunity think through and make a mental image of what needs to be done for me to answer these questions. This document, containing only headings loosely structured notes, will eventually grow and evolve into the finished paper.

Step 2: Research and note-taking

This stage involves data collection or other information gathering, reading up on related research, and doing experiments and analysis. Exactly what this step entails and how much time it takes depends on the nature of the paper. It is not the focus of this post since we are here concerned specifically with writing. The important point I want to make here is that during this research phase I take a lot of notes that I write under the appropriate headings in the document described above. Again, these notes are very simple: short abbreviated sentences or lists. These notes include how I actually do the research, so that I can later describe it in detail in the method section, and what the findings are that I want to present. If I get ideas about how to write the introduction or the conclusion, or randomly come up with some clever formulation that I might want to use somewhere in the paper, I also jot that down in the appropriate section.

Step 3: First write-up

Having done the research, I go through my notes, move them around if necessary to their appropriate parts in the structure, and start connecting them with text, fleshing it out to something resembling continuous readable prose. Note that I do not call this step drafting, because that might imply that the text is then in a state where it could be read by someone else. Most of the text produced in this step is still really bad prose, and intentionally so. The point here is to collect a bunch of coherent text that can later, in the next step, be reworked into good prose. The text should, however, in this stage contain all the core parts of the paper in one form or another.

Some people find it difficult to start writing a new text. I have never experienced this. Having taken plenty of organized notes during the research phase in Step 2 means that I don’t start with a clean document trying to find the first word. Rather, I start with a bunch of statements and try to connect them. I don’t even start at the beginning, but let the document grow from inside out instead of from beginning to end. If I don’t find ways of connecting some of the notes now, I leave it for later.

I think of this step of connecting the notes and writing them up in continuous text as me explaining the idea of the paper to myself. This typically reveals things that I hadn’t realized were lacking in the research, or things that I hadn’t thought of before that are needed for some explanation to make sense and for some reasoning to follow a logical sequence. This could, for example, be some method I should have tried out, some additional material that would logically fit in the research, or a concept I realize I don’t know well enough to apply or to explain in a concise and accurate manner. I then go back and redo steps 2 and 3 again for these parts.

This step also involves a lot of moving things around, since you tend to see clearer where certain statements or explanations fit when you have it laid out in text.

The introduction and the conclusion may still be missing at this point, or be in a very rough state. They are for me the most difficult parts to write, and they depend heavily on how the rest of the paper turns out, setting up or concluding things yet to be written. They also, more so than other parts, need to be adapted to the audience and the journal I submit to, which I may not have decided at this point.

Step 4: Editing

After Step 3 (with potential iterations of steps 2 and 3 for some parts) I end up with a coherent but poorly written text. Now it is time to print it and go at it with a pen. I prefer a pen with colored ink because I like how it looks on the page. I like to do this at a café or, depending on the season, outside in a park or by the sea. Being able to work in a beautiful environment is one of the perks of the trade.

In going through the text from start to finish I, among other things,

- mark with arrows things that should be moved

- reformulate clumsy-sounding sentences

- shorten over-long sentences

- correct spelling mistakes

- expand on things that need further explanation or that need to be illustrated with some example

- note terminology or other wording that needs to be standardized, so as to later fix this with the search-and-replace function on the computer

- check that repeated listable material is always presented in the same order (for example if you are comparing three authors, it is easier on the reader if they are are always presented the same order, in explanations, lists, tables, and what have you)

- remove closely repeated repetitions

- add repetitions as reminders to the reader of ideas developed on distant previous parts of the paper

- check the suitability of examples, so that they, for instance, do not include and call attention to features that are not under discussion and that may distract the reader

- check that the citation engine has done its job correctly

- note things that I need to look up in the literature or in my data

For a paper of twenty or so pages, it takes the most port of a working-day to do one editing pass, but I find I often do not have the energy to do it all in one day.

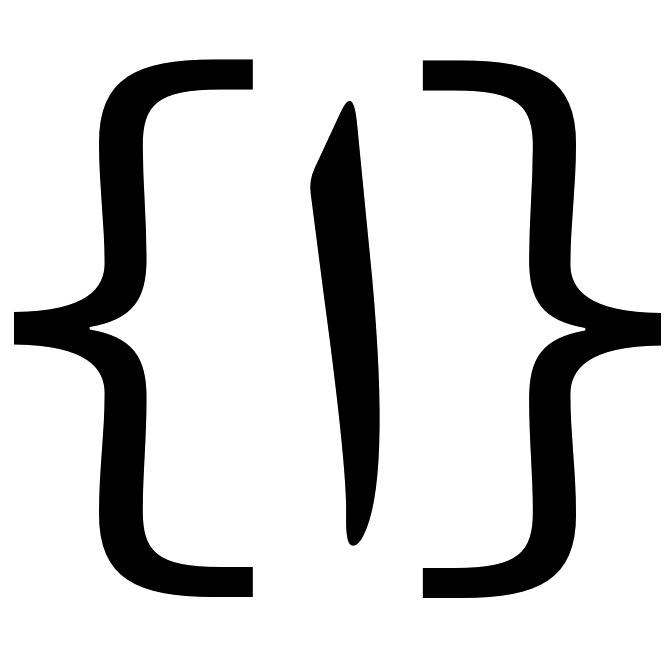

The image below shows a typical example of a page of text after one pass of editing.

On the surface, this editing is a process of improving the language and style of the paper. While this is certainly part of it, it is also a method for thinking deeper about the material. Organizing the text, even at the clause or word-level, or choosing the right wording to express an idea as exactly and unambiguously as possible, all part of editing, require deep and intense thought about the material. In my experience, editing is therefore deeply intertwined with and an inescapable part of systematic thought, and a core part of the intellectual labor of any research project.

When I have edited the entire text with pen in hand, I then insert the edits into the electronic document. To some extent this is a simple data-entry activity, but it is also an opportunity for further edits and to reevaluate the edits done on paper, now when I see how they read when inserted in the text. However, even the more mechanical entry is oddly satisfying, as I see how my handwritten notes gets integrated into the text and I watch it grow and develop in front of me.

For a typical paper I repeat Step 4 around five times. My printer runs warm. This might seem like a lot of boring work, but seen from the perspective of editing as the expression of thought, I find it enjoyable, and often challenging. It involves a lot interesting text-structural and linguistic problem solving and frequent micro-reviewing of the literature.

Somewhere between editing passes I go through the text to format it to the journal’s requirements, changing the font, paragraph formatting, putting tables in a separate file, and such. This can be a nice break from the demanding thought-intensive editing.

At some point, after many passes of editing, I reach a threshold of diminishing returns. Also, after having read through the same text (or different versions of it) multiple times I start to become blind to it and can no longer evaluate it or see it from the perspective of a person reading it for the first time. If at this point I am happy with it, I go to Step 5. If not, there are two options. The first is to let it rest for some time, preferably couple of weeks, before going at it again with fresh eyes. The second option is to have a colleague read it and give comments. This latter option may result in me re-evaluating and rethinking some major aspects of it, which requires more passes, perhaps focused on specific parts of which the colleague was critical. After this, I move to Step 5.

Step 5: Proof-reading

Proof-reading is a special kind of final editing pass at which I am spectacularly bad. But it needs to get done. I find it helps to print the text in a different font and to read it aloud slowly, focusing on articulation, and to have the computer read the text aloud back to me. It is best is to also have someone else, preferably a professional proof-reader, give it a final check. In this step I also carefully go through the generated bibliography to see that it has been rendered correctly.

When proof-reading, I try not to do any other types of edits, but I inevitably end up doing some. These are typically small things. Any larger edits, while possibly improving the text, will at this stage likely only have a small or questionable benefit, and are for the most part not worth the effort.

Then I’m done. (Well, until the reviewers and editors have their say.)

I do mean a lot of editing

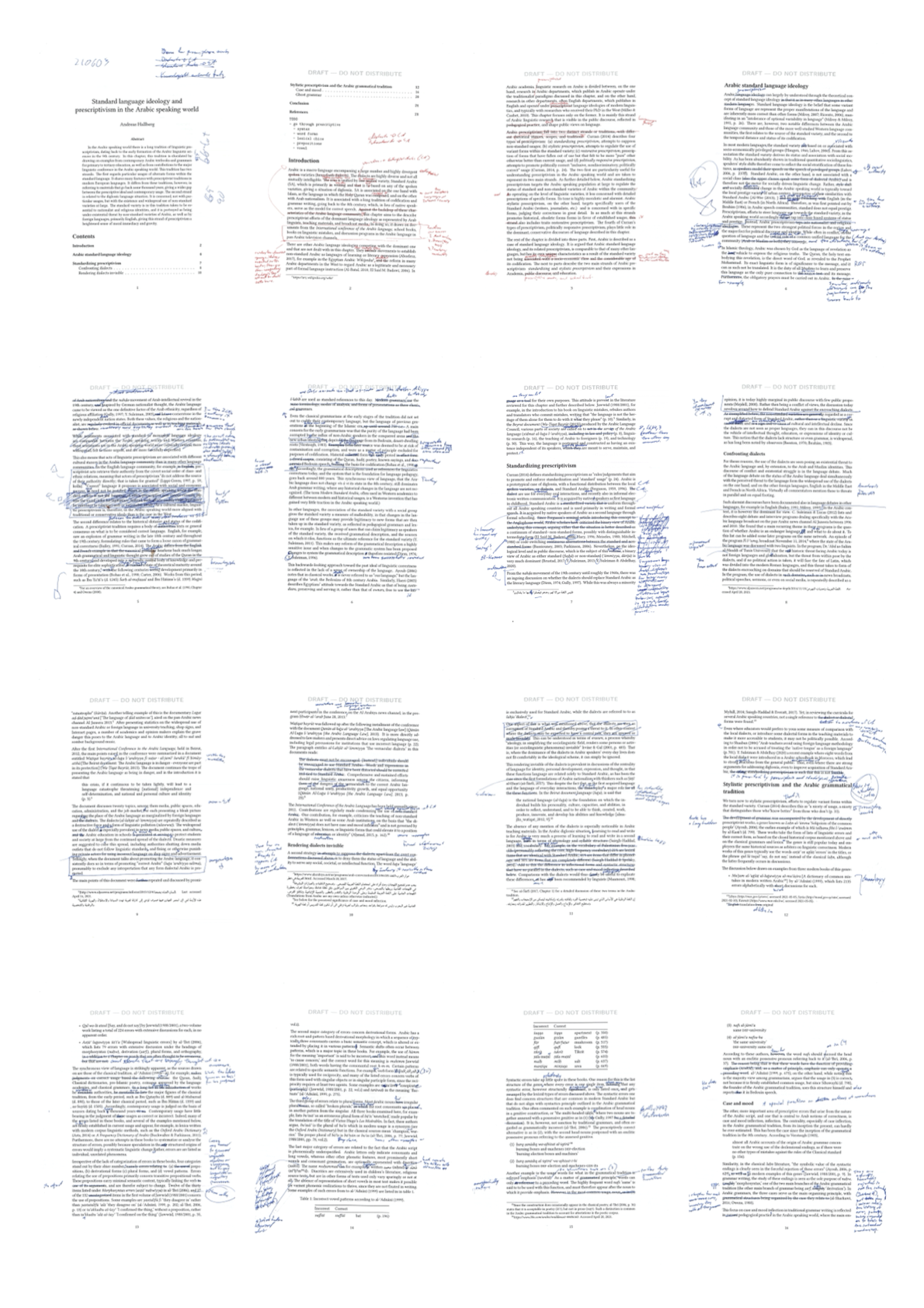

To drive this point home, the image below shows the first sixteen pages, of a total of around twenty, after the first editing pass. I did five editing passes for this paper, including one pass after reviewer feedback, so roughly one hundred edited pages in total.

Looking at edits like these, after the fact, I always find them strangely intriguing. Part of it is probably that they represent all the work I have put into the text and that they are therefore something to be proud of. Part if it is also that they present a visual representation of all the accumulated thought, as it was filtered, condensed, and molded into the final text.