Visualizing Badawī’s model of linguistic variation in Arabic

In his highly influential book Mustawayāt al-ʿarabiyya al-muʿāṣira fī miṣr [The levels of contemporary Arabic in Egypt] (1973), Saʿīd Badawī presented his theory on the relationship between Standard Arabic (fuṣḥā) and vernacular Arabic (ʿāmmiyya). The model has become a staple of modern Arabic linguistics, duly covered in textbooks, monographs, and review articles of Arabic sociolinguistics and related fields. At the core of Mustawayāt is a figure that illustrates his model. It is reproduces also in his later publications (Badawi 1985, 1986). While the main gist of the figure is easy enough to grasp, there are some aspects of it that I for a long time could not quite understand. I later realized that the figure is in fact poorly designed. In this post I describe the problems with the figure and present a suggestion for how it can be redesigned to better convey Badawī’s theory.

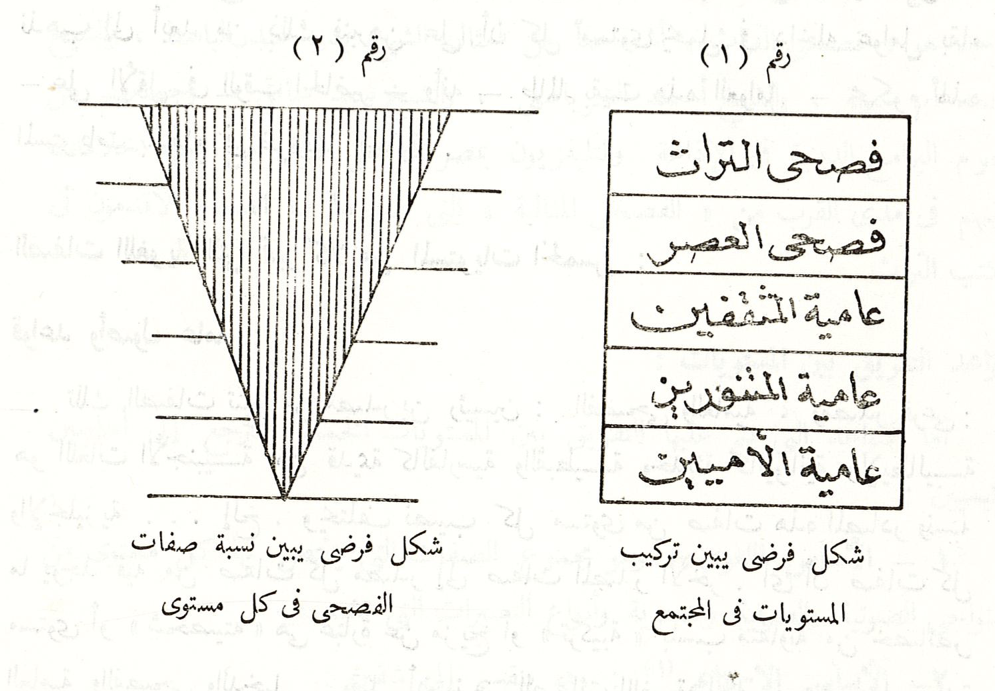

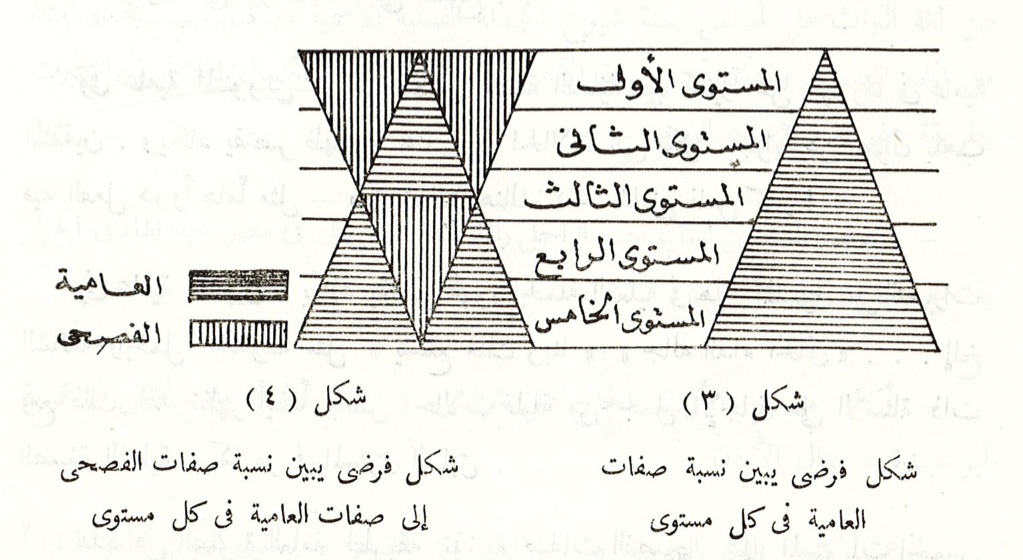

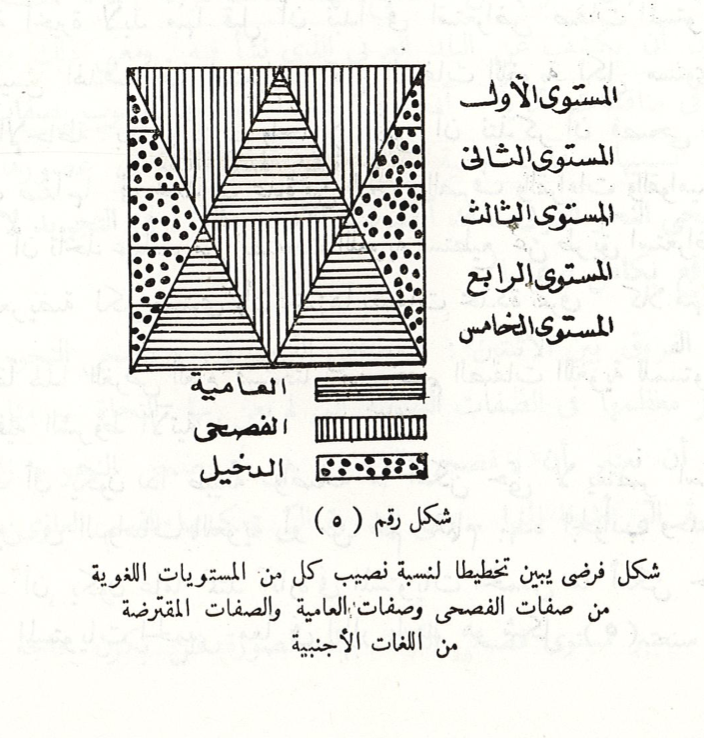

In short, Badawī’s theory of levels of Arabic states that different forms of Arabic can be described as occupying a position on a scale between on the one hand traditional Classical Arabic, and on the other non-standard or vernacular Arabic. Badawī describes five levels within this system: “pure” classical and “pure” vernacular, at the top and bottom, and three levels in between, ordered according to the proportions of standard and vernacular features they contain. The middle level, Educated Spoken Arabic, is characterized by an even mix of Standard and vernacular Arabic linguistic features. This middle of the spectrum also has the highest proportion of loanwords, with the amount of loans decreasing as one moves towards the top and bottom levels. These five levels are associated with different domains and segments of the population. For example, only the illiterate speak the “bottom” form, with minimal Standard Arabic features and few loan words, and only Islamic scholars use the topmost level of pure, traditional Classical Arabic.

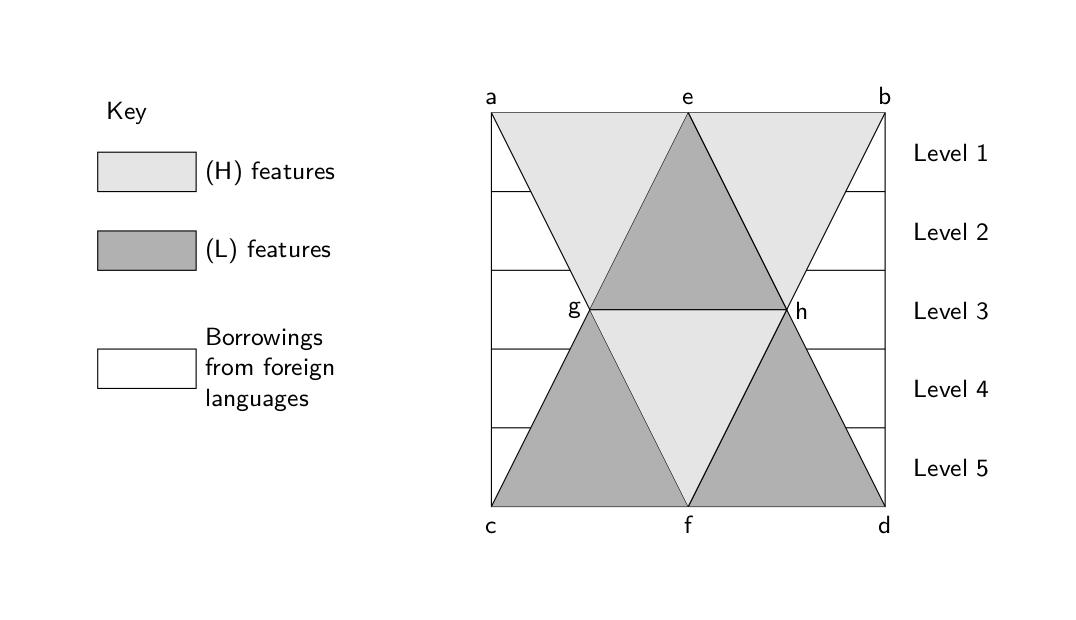

In the book, these levels are presented in a series of figures that progressively build up the complete figure which illustrates the whole model. First it is shown how Standard Arabic features decrease towards the lower levels:

Then this is combined with the reverse triangle representing how vernacular features increase towards the lower levels:

Then the rest of the area is filled up with loan (dotted). This illustrates how loans are more plentiful, and make up a larger chunk of the total language, in the middle levels:

The following is a reproduction of the figure as it appeared in a later article in English (Badawi 1985). Here I have used shades of gray instead of the original vertical and horizontal lines to differentiate ares.

Now, typically a graph like this one is meant to be interpreted two-dimensionally, with the size and extension of each area in the two-dimensional coordinate system representing the size and extension of each theoretical object. Since there are only two dimensions, things cannot overlap. In this figure, the y-axis represents the diglossic continuum, and the x-axis represents the proportion of Standard Arabic features, non-standard Arabic features, and foreign loans, on any given point on this continuum. The proportions of Standard Arabic features increases, and the proportion of non-standard features decreases, as one goes up the scale.

However, to get this interpretation we must parse the figure as having three dimensions. The triangles representing Standard Arabic and vernacular Arabic features overlap and pierce through one another, and there are parts of them we do not see. They are above and below one another. There is therefore a third dimension of depth in the intended interpretation.

The areas on the sides, representing foreign loans, are however not to be interpreted as being three-dimensional. One is tempted, when looking at the figure, to also interpret this see area as three-dimensional, as one continuous area covering the background of the entire square, overlapped by the two triangles. The intended interpretation of this area is, however, as opposed to the other two areas, not as existing in three dimensions. Only that which we can see is there; there is no overlapping. Having parts of the figure existing in three dimensions and other pats two dimensions makes this figures difficult to interpret.

Another problem is that even the intended interpretation produces strange results, with some levels containing more than 100% features. The lowest style (point c to point d) contains (theoretically) 100% vernacular Arabic features. The highest style (point a to point b) contains 100% Standard Arabic features. Level 3, or Educated Spoken Arabic, right in the middle, contains a mix of vernacular and Standard Arabic features as well as loans. However, given that the two triangles overlap, this level contains more language than the top and the bottom levels. A horizontal line across the middle of the figure, representing Educated Spoken Arabic, contains the left edge to point g (loans); the right edge to point h (more loans); and point g to h twice, once for Standard Arabic and once non-standrad Arabic, since these two triangles overlap. Educated Spoken Arabic thus contains more than 100% features, 150% to be specific. I do not think this is an intended effect.

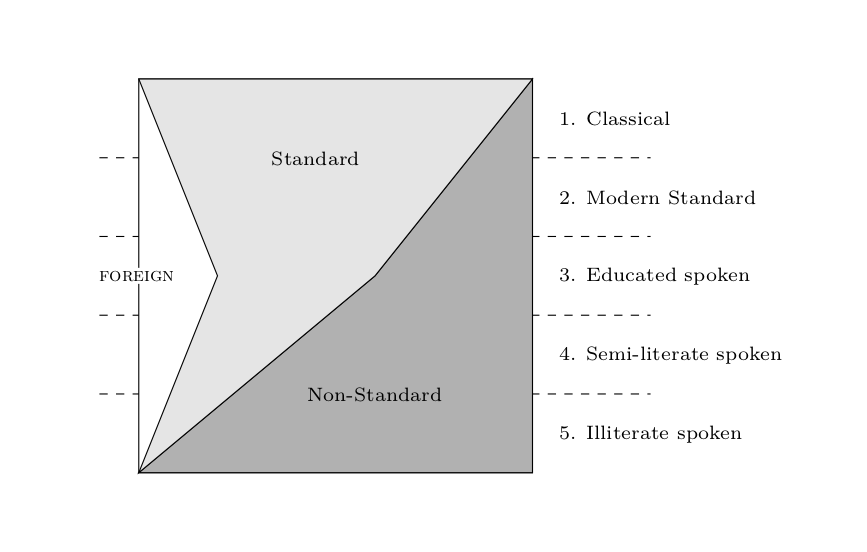

An alternative design of the figure that does not have these problems is the following:

In this redesigned figure

a) the relative proportions of Standard and non-Standard Arabic features and loans are as described in the theory (e.g. the level in the exact middle has equal proportions of Standard and non-standard features, loans increase in the middle and decrease towards the top and bottom);

b) everything is consistently mapped in two dimensions; and

c) no level (as represented by any horizontal slice) has a sum of features of more than 100%.

This redesigned figure is, I believe, a better representation of Badawī’s theory of linguistic variation in Arabic than is the original figure.

References

Badawī, S. M. (1973). Mustawayāt al-ʿarabiyya al-muʿāṣira fī miṣr. Cairo: Dār al-Maʿārif bi-Miṣr.

Badawi, S. M. (1985). Educated Spoken Arabic: A Problem in Teaching Arabic as a Foreign Language. In K. R. Jankowsky (Ed.), Scientific and Humanistic Dimensions of Language (pp. 15–22). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Badawi, E.-S. M., & Hinds, M. (1986). A Dictionary of Egyptian Arabic. Beirut: Librairie du Liban.